News this week: Yelp IPOs. Friday's close was $24.58, 59.9 million shares outstanding, giving the company a market capitalization of $1.5 billion. In eight years, I hear, they have yet to turn a profit. So, what on earth are people buying? Shares...

Google sells for $

621.25 a share, maket cap of $202 billion.

Apple sells for $

545.18 a share, market cap of $508 billion.

Amazon sells for $

179.30 a share, market cap of $81.6 billion.

What is the value of those shares? What exactly do you own, when you own shares of Google or Apple, Amazon or Yelp? Each one is worth one ticket to an arena with 59 million, 300 million, or 900 million entries. That's 3,000-45,000 Madison Square Gardens! One vote in an ocean of votes. That's ownership I suppose. What other benefit do you receive? You don't share directly in the profits. They pay no dividends.

Price earnings ratio is often quoted as a means to value shares, with 15 x earnings being a conservative target.

- Apple at a P/E of 15.53 is pretty close

- Google with a P/E of 20.89 is only slightly worse

- Amazon's P/E of 130.60 is rather extraordinary

You can think of it like interest in a savings account. If the companies paid out 100% of their profits as dividends, it would take you 15.53 years to double your purchase price of Apple shares; 20.89 years to double your investment in Google, or a whopping 130.6 years to get out what you paid for a share of Amazon. To put that in perspective, a P/E of 15, with 100% of earnings paid out in dividends would be roughly the equivalent of earning about 5% compound interest on savings, quite attractive in today's market.

But then, that assumes 100% of earnings are paid in dividends, not normally the case. Or it assumes that the earnings will increase dramatically over time, and thus the dividends paid will likewise increase. But in many cases, 0% is paid out in dividends, leaving a shareholder with no direct benefit from owning the shares. Unless these companies at some point begin paying dividends, shareholders' potential benefit only accrues upon selling the shares. Your sole means to profit from owning these shares lies in your ability to sell those shares to someone else at a higher price than you paid. Someone else who would likewise have no ability to share directly in the profits of the company. What is that like? Let's see:

Say it's 1988: Cabbage Patch Kids have been around for a decade. You buy a dozen or so, as collectibles. $15 a pop, leave them in their packaging, with the hope that a few years later, you'll be able to sell them for $25 or $50 or $100 each!

What's the difference? To be honest, I can't see any. To be more direct:

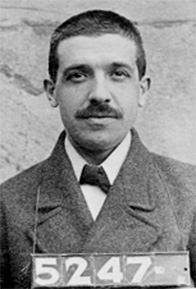

A share's value must be the present value of all future dividends--otherwise

stockmarkets would be a giant Ponzi scheme.

--The Economist, March 7, 2009

In the dot.com boom the argument was that young, hot, technology companies were forging new territory, and should be allowed to reinvest in their own growth, which down the road would be translated into profits for the shareholders. But then, Google, founded 1998 is already 14 years old; Amazon founded in 1995 is 17; and Apple, with its origins in the Bicentennial is solidly within Generation X at 36 years old. Just when do you expect they will start paying dividends?

And if never, are you really willing to continue participating in a Ponzi scheme?

For my part, I have every intention to reduce our vesting in the market, which currently stands at about 80%, down to about 40%, strongly preferencing those stocks and mutual funds that currently pay dividends, or whose young companies represent an innovation I believe in (like Tesla Motors). What will I do with the remainder? I think I'll invest in my own current business or start a new one. I was never much one for Cabbage Patch dolls.